Faster Than a Speeding Adverb

June 20, 2024 § 30 Comments

By Ronnie Blair

As a boy in the 1960s, I enjoyed few things better than buying 12-cent comic books and immersing myself in the adventures of Spider-Man, Batman, the Flash and the Avengers. The crimefighting and universe-saving drew me in, but the cheap pulp-paper pages had other enticements as well: advertisements for X-ray glasses, Sea-Monkeys, and the Charles Atlas muscle-building method that would “make you a new man.”

The best feature of all, though, was the letters page, where comic book readers mailed in their praises and criticisms.

The idea that my name and my words could appear in a comic book was intoxicating. One day, filled with eight-year-old hubris, I took a piece of lined notebook paper, picked up a yellow No. 2 pencil marred by bite marks, and scribbled my thoughts about a story in one of DC Comics’ Superman titles.

I am unsure what intellectual insights I shared with the DC editor, but I placed my letter in the mail, confident that the U.S. Postal Service would grasp the magnitude of the moment and whisk my words off to New York City without delay.

Then I waited. Weeks passed. I read more comic books and more letters to the editor, always with the knowledge that my letter was out there, by now in the hands of an impressed editor eager to share my third-grade brilliance with Superman readers.

The day arrived when my letter should appear and I bought the issue, skipped past the story and the Sea-Monkeys ad, and turned to the letters page to revel in my victory.

Except there was a problem.

Several letters appeared from readers commenting on the issue that I had written about – and with nowhere near the same flair, I am certain – but my name and words were not to be found. Instead of admiring my epistolary efforts, some jaded editor had tossed my letter into a wastebasket. Perhaps New York City rats exploring a back-alley dumpster had the chance to marvel at my writing.

Who had I been kidding? Sophisticated comic book editors had no need for the prose of 8-year-old boys living in the Kentucky back hills. The failure stung and, with that single rejection, I gave up comic book letter writing.

At least I did until March 1972 when, for reasons now forgotten, I gave it another go. I was 14 and that extra six years of wisdom allowed me to approach my mission strategically. It had been a mistake to target a popular Superman title with stiff competition from other letter writers. The smart thing was to zero in on a less-beloved comic book. I turned to Weird War Tales, a newer comic that mixed the military battlefield with the supernatural.

By now I owned an electric typewriter. I positioned my fingers on the home keys, just the way my eighth-grade typing teacher instructed, and wrote:

I have just finished reading Weird War Tales #5, and I thought it was great. Once again you have printed a comic that exceeds all others in this category. Your theme about escapes has been the best since this comic started. I especially liked “The Toy Jet.”

Admittedly, the prose did not hum. Introspection was lacking. But it was at least succinct and grammatical. I folded the letter, tucked it into an envelope, and walked to a mailbox that stood at a street corner near my house.

Life continued. I finished eighth-grade and spent the early summer days swimming in a river with a pal. He and I explored our small world, walking the railroad tracks from one part of our coal-mining community to another, playing basketball at neighborhood hoops or challenging each other to footraces in the hills. And then one day I entered the Rexall drugstore where a new shipment of comic books had arrived. On the spinner rack was Weird War Tales No. 7. I turned to the letters page, haunted by memories of an 8-year-old’s dashed hopes, and scanned letters submitted by readers from Glendale, California, and from Seattle, and from Seattle again.

Then there it was. My letter. My words. My name. My hometown.

Around me, oblivious drugstore clerks and customers went about their lives as if this were just another ordinary day. As I paid for Weird War Tales No. 7, I resisted flipping open the comic book and showing the cashier that this was a historic moment the store needed to record for posterity.

Over the next few years, I wrote many more letters to comic books. Most shared the same fate as my earliest effort, but more than 20 saw print. They served as preparation for an eventual career as a journalist and my work today as a public relations writer. The comic book editors on the receiving end of my letters taught me a valuable lesson. Rejection never feels good but it is not kryptonite.

You will emerge heroically to write again.

________

Ronnie Blair is lead writer in public relations for Advantage Media and Forbes Books. Previously, he worked for daily newspapers for more than three decades. He is author of the memoir Eisenhower Babies: Growing Up on Moonshots, Comic Books, and Black-and-White TV.

Getting Ready for My Close-Up

June 19, 2024 § 7 Comments

By Lisa B. Samalonis

The phone rang an hour after my essay on buying a home for myself and my two sons after divorce went live. The caller ID had a (212) area code: New York City.

Reflexively, I let it go to voicemail.

Minutes before I had received an email, a LinkedIn request, and tweet from producers at a major national morning news show: Good Morning America.

Was this some well-coordinated prank? Or was it really a GMA producer calling me, a camera shy and video averse essayist who writes alone from behind a computer screen in her home office? My stomach tightened as I listened to the message.

The producer said he saw my essay, “I lived paycheck to paycheck after my divorce. By making some tweaks, I was able to buy a home for my kids,” published on a business and parenting website and subsequently reposted on Yahoo’s headline daily news that same morning. He invited me to be interviewed later that day for the GMA’s money segment scheduled to air the following day.

Facing My Fears

Even though I have been publishing essays in magazines, newspapers, and on the web for years, I had never been invited to appear on television and frankly, that was just fine with me. I prefer to create in the quasi-anonymity of my suburban existence. However, the personal finance topic in a down economy had generated buzz. The producer noted in his message that the morning show’s audience loved a good money story about a mom who budgeted successfully. My essay’s attention-grabbing headline (written by the website’s editors) enumerated several tips that helped me afford a new townhouse after getting divorced, paying off debt, and regaining control of my financial life.

I called my oldest son and a few friends before returning the producer’s call. My son revealed that the producer was ringing and emailing him to get a hold of me as well. That was both flattering and alarming.

“I think it is legit, mom,” he said. “You should do it.”

My friends agreed. “How can you not?” and “You can’t let this pass you by.”

I looked around my messy office. I had been working remotely for several years. I hold a full-time job as a medical editor in addition to my freelance writing gigs. I could stage the room for the video backdrop easy enough, but could I quell my anxiety to seize this opportunity.

As a journalist, I am usually the one conducting the interviews. I had no formal media training as an interviewee. What if I looked ridiculous and fumbled over my words or misspoke so my meaning was unclear?

When I returned the call, the producer explained this would be a short, taped segment interspersed with a voice over and some pictures of me, the house, and my sons. I agreed to do the interview despite my nerves. The producer handed me off to the segment producer and we set up the interview for the next day as that day’s breaking news had bumped the schedule.

This provided an extra day to prepare. I watched media training videos on YouTube and made a list of the bullet points I wanted to share. I also considered my personal boundaries—like details I didn’t want to disclose about my divorce.

Sharing the Message

I write essays about raising sons as a single parent because I have been changed by this challenging, yet wonderful, experience. My bond with my sons has been forged through difficult times and has required perseverance, a collaborative effort to problem solve together, and radical honesty between us. I write to connect with other people who have experienced or are experiencing similar things.

I also write to inform others who might not understand the single parent perspective. But I reminded myself that appearing on television to talk about my essay was about the message, not me. After my divorce, I learned to better manage my finances which helped me create a stable life for my children. I wanted to encourage and educate others.

As I spoke with the segment producer, I mentioned my reservations of getting flustered, speaking too fast, and muddling my message, and she assured me her job was to produce the best segment possible and that included making me look and sound good. I emphasized that the point of my essay was to empower people to live their best life and directly face their financial situation despite fear.

Welcoming New Opportunities

Ultimately, the segment ran about five minutes, and I communicated as effectively as I could. I didn’t tell many people before my TV debut, but friends, family, and colleagues saw it and called to tell me it was great. Plus, it was picked up by local and national ABC affiliates and repurposed into other articles across internet. And after that I got invited to be a guest on a financial podcast, which was another first.

Yet for me this experience was less about my five-minutes of televised fame, and more about challenging myself to say yes to an unexpected opportunity to share the message of my writing in a different medium. Although I am not sure my nerves could take a repeat performance on national television anytime soon, I am glad I pushed the writer me—shy and (still somewhat) video averse—out from behind the anonymity of the computer screen and in front of the camera to embrace my close-up. This has led me to think: what might I do next? And, of course, what will I wear?

__________

Lisa B. Samalonis is a writer, editor, and essayist from New Jersey. Her essays have appeared in Insider-Parenting, Next Avenue, The Independent, and The Philadelphia Inquirer among others. Connect with her on LinkedIn, X, or subscribe to her newsletter.

The Map We Carry: Writing Place

June 17, 2024 § 8 Comments

By Sonya Huber

Yesterday I drove from my hometown of New Lenox, Illinois, to Columbus, Ohio, a six-hour drive that I’ve made many times over the past twenty years. Sometimes I drove alone, singing over the noise of the wind rushing in the windows of a red pickup truck with no air conditioning, and later I drove with my son strapped in the back car seat as he grew and grew. The drive is as familiar to me as the lines on my palm: western Ohio along I-70 to the woods of eastern Indiana, to the circle around Indianapolis and the angle of I-65 that threaded northwest into the flatness of central Indiana with its hopeful windmills and its alarming billboards to the knot of I-80 that girds the southern border of Chicago.

What IS place, anyway? It’s an aggregate of the dirt beneath our feet, the decay built by aeons of plants and the crashing and boiling of minerals and stardust, the ebb and flow of species as they adapt to what they find. It’s where our feet are, where the forces of the universe anchor us so that we can have what we call “a life” and where our remains go when that life is done. It’s often the nearest expression of spirit, or wildness, or comfort; it can also be a prison, a gulf of miles that separates us from who or what we love; it’s a record of humankind’s wrongs, its violence and its erasure.

I thought about place a lot as I drove, singing along to John Cougar Mellencamp as he always emerges from the radio in Indiana, as I listened to the accents of announcers and advertisers shift from the beloved clipped-and-nasal Chicago accent to the broad southern-tinged of central Indiana. I tried to capture the love and heartbreak of being tied to a place in my recent book, Love and Industry: A Midwestern Workbook, and that’s what I focus on when teaching the craft of writing place.

I am fascinated with the way a place that is familiar gets under our skin and provides the materials to build our skin, bodies, and minds. I am fascinated with the way travel can peel off our skulls so newness can seed inside, but also the way in which a deep relationship with a known place changes over time, and the way in which these long relationships grow over scars and hurts as real, complex, and as contradictory as any human relationship.

Space and place are, if we step back a little, fundamentally mysterious, and physics now sees “spacetime” as “a mathematical model that fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional continuum.” When I think about traveling over and over on this route, like an electron circling a nucleus, and think about the likelihood of me being here, and what it entangles me with, what unseen forces hold me here and yet also pulled me away, I can see place as a mystery, a longing, or a portrait, as the writer André Aciman describes in his beautiful book Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere as a “wishfilm” that adhered to the cities he loved (and I think he might links this to, or draw his ideas from the philosopher Walter Benjamin, but as I am writing this on my friend Jenny’s dining-room table in Columbus, Ohio, I don’t have access to that book—just the traces and paltry bits left on the Internet’s surface and the bits and pieces that mapped onto the synapses I carry.)

The nature of storytelling changes when you use place as a lens, rather than narrative over time, creating what Native American scholar and philosopher Vine Deloria, Jr., describes as “what happened here” instead of the Western view of “what happened then.”

Many of us experience a worldview in which place is setting or backdrop, the decoration or stage on which human action occurs. But place can give us not only details and sensory elements on which to tell a story; it can also give us new ways of seeing, hearing, remembering, and understanding the stories of our lives.

________

SONYA HUBER‘s new essay collection is Love and Industry: A Midwestern Workbook. She’s also authored Voice First: A Writer’s Manifesto, and the award-winning Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, The Atlantic, The Guardian, and other outlets. She teaches at Fairfield University and in the Fairfield low-residency MFA program.

Come join Sonya to get really weird and reverent about the craft and art of writing place in her webinar Writing Place: Make Setting Come Alive for CRAFT TALKS on June 19 at 2PM Eastern. Register now ($25)/more information.

Writing Difficult Stories: How Do They Do It?

June 14, 2024 § 21 Comments

By Diane Reukauf

“When we write our stories, we change the way we carry them.”

That’s what Melanie Brooks said at the end of an AWP panel she moderated a few years ago. I wrote those words in black ink on a 3×5 card that I kept on my desk while writing a collection of fragments about my granddaughter’s sudden death a decade ago, just weeks after passing her four-month checkup.

Earlier, I had read Brooks’ first book, Writing Hard Stories, based on interviews she conducted with 18 authors. She was struggling to write about a difficult period in her life and was concerned about the emotional costs of revisiting the pain. She wanted to know how other writers faced that challenge.

One author said he initially kept a safe distance from the more painful details, and the result was flat narrative. All spoke about how grappling with their experience gave shape to their stories, often a shape they hadn’t imagined. While the writing itself did not erase the suffering, it was in this shift that they discovered meaning.

I was already writing about Louisa’s death when I read Brooks’ book, but sadness and misgivings had begun to swirl and slow me down. The words from those authors encouraged me to push forward.

So, I kept writing.

And then two years later I stopped. Not because of that thing called writer’s block. It was writer’s confusion. I’d already written and rewritten over 50 pieces, but something was missing. The story had not taken on a meaningful shape. What was I failing to see?

It was a relief to step away, and I considered giving up entirely—but what I really wanted was a way forward.

I picked up Melanie Brooks’ second book, A Hard Silence, in which she recounts the story of her surgeon father’s diagnosis of HIV after receiving contaminated blood during open-heart surgery in the 1980s. Not wanting his wife and four children to suffer the consequences of HIV/AIDS stigma, Brooks’ father took on a non-surgical position and moved the family away from their hometown—determined his infection would remain a secret.

Brooks was 13 years old when her father was diagnosed. As she moved through her teen years, she needed to ask questions, to talk openly within her family, but for years the secret seemed to persist even between family members. She lived inside that silence for almost a decade before her father died.

In A Hard Silence, Brooks shares the confusion and isolation of those years. We witness her struggle to make sense of the pain that followed her well into adulthood, and we see her today as a wife and mother acutely aware of the cost of keeping a solemn secret inside a family.

Two things became clear in my second reading of this book. I noticed the way the writer told her story, not the family’s story. And I saw how it was the examination of her own pain that guided her search for meaning.

And then it struck me. I, too, had been keeping a secret—even from myself. I thought back to a time when a few writer friends read my early attempts at writing about Louisa’s death. Each asked the same question: “Where are you in this story?”

I thought the focus of my work was obvious. I was writing as an observer of events, reporting from a distance about the devastating effect my granddaughter’s death had on her family. I intended to tell their story. I hoped I might discover what this shattering loss meant so I could turn to my daughter one day and say, “Here, I’ve figured it out.”

It was a naive goal.

While my grief is attached to my daughter’s, the only story I can tell with any authority is my own. For too long I failed to examine who I was in the narrative—a woman lost, scared, and shaken by my limitations in the face of an immense loss. Before I could give shape to my story and hope to discover meaning, I’d have to examine the threads of my own grief.

I turned to other memoirs on my shelf, focusing on beginnings and endings. How did the writers do that? How did they find their way to make something new, something worthy, out of their losses and their suffering?

I have now returned to the challenge of writing this story. I write as a witness to the overwhelming impact of a baby girl’s death on her parents and her young brothers, but I also write as a mother powerless to lessen my own daughter’s pain and sorrow. I write to give meaningful shape to a devastating loss—aware that in the writing I might change the way I carry it.

—

Diane Reukauf’s essays have appeared on the Brevity Blog, WOW! Women on Writing, and in print versions of Skirt! and Parenting Magazine. She is co-author of Commonsense Breastfeeding and The Father Book: Pregnancy and Beyond. Her dissertation, The Mother’s Voice in the Progressive Era: The Reform Efforts of Kate Waller Barrett, received the Outstanding Dissertation Award at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education. She has conducted expressive writing sessions for international college students, female faculty members, and pediatric oncology nurses. She is currently working on a collection of pieces about grief and motherhood.

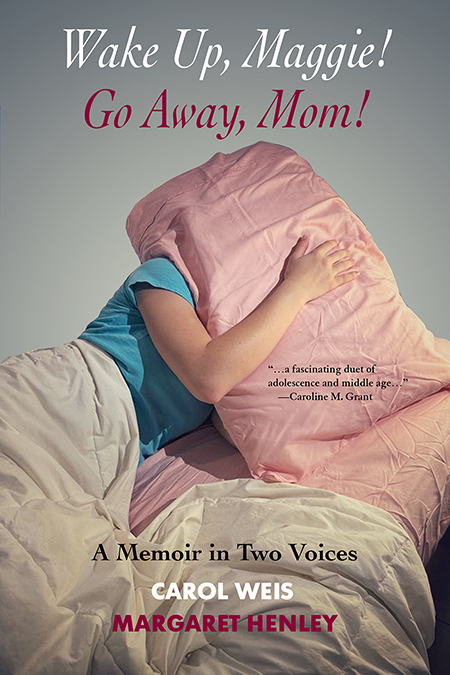

Writing a Memoir With My Daughter

June 12, 2024 § 20 Comments

By Carol Weis

My daughter was five when I got sober. Her dad left four months later. It was a difficult time for us, one that I processed by writing, something I’d never done before. It started with primitive poetry, like a 4th grader might scrawl. But it helped move me through some of my grief. Feelings I didn’t want to take out on my only child.

Fast forward 10 years. And this will come as no surprise—this child, who sat on my lap until she was 14, was now in high school and wanted little to do with me.

To keep us connected, I suggested we start a parallel journaling project, each penning our grievances, plus tidbits of news from our daily lives. A project Maggie first agreed to, but soon lost interest in. Then following another one of our daily fights over internet access, we took a break and went to our favorite bookstore. And upon Maggie’s suggestion, we came home with two cool-looking journals, one for her and one for me.

We agreed to write in our journals at least twice a week and most importantly, I could not tell Maggie what to write. I broke that rule a number of times when I thought we should each write about our perspectives on certain events, like a fight we’d had or even the presidential election.

We worked on the endeavor for two years and it wasn’t always smooth sailing. It became one more power struggle. There were fights. Once a chair got raised (and possibly thrown) by this frustrated mom. But we managed to make it through to her freshman year in college. And that’s when I decided to turn our journal entries into a memoir, naively telling her we could use the money to help pay for college or take a trip together.

We knew that to turn our project into a memoir, we would need more material. During Maggie’s first year of college, I’d send her an idea, a memory, or a draft of something I’d written. She’d either respond or write her own memories of the incident. On another occasion, Maggie watched a movie at her dad’s that triggered some of her childhood trauma. She wrote me a letter filled with her sadness. We put that in the manuscript, too. Also, she was taking a poetry class that year and had written a few good poems. We decided to intersperse our manuscript with poetry, depending on how the topics fit.

The hardest part of the process was transcribing our entries. It was painful to read my daughter’s and often just as painful to read my own. But I pushed through because I thought we had something others would connect with and might help them heal some wounds. Like it did for us.

Eventually, I hired an editor, a woman I’d met at a party, a writer who had worked at The Atlantic Monthly and who was enthralled with our concept. She recognized its need for repair. For almost a year, we trekked through four rounds of revisions, as she urged us to go deeper, to make the journaling read more like a novel, to develop story arcs as we went along, each drama having its own curve.

I wrote an introduction to our memoir, then passed it onto Maggie to give her own take. When some family members we’d written about died, we thought it wise to write an epilogue, each in our own voice, giving our different viewpoints.

We played with many different titles. Our working title through much of the project was Same Landscape, Different Views, supplied to me by a good friend. When my writing group—who had listened to me read the manuscript over a two-year period—suggested Wake Up Maggie! Go Away Mom!, both my daughter and I embraced it right away. The subtitle was a different story. The Dueling Diaries of a Teenager and Her Mom, The Dueling Diaries of Two Control Freaks Trying to Let Go, and A Story of Letting Go were just a few.

Many times, I wanted to give up. Many times, I thought how lame it was to even think about getting it published. But I tried for four years, even found an agent who loved the idea of our parallel journaling project and thought she could sell it. Meanwhile, my daughter had abandoned all hope of it ever becoming a book. Instead, she persuaded me to write a memoir of my own, which I started in 2014. To my delight, Heliotrope Books, an NYC indie publisher, accepted and published that memoir in 2021. Unfortunately, it had taken all the energy away from our dual project.

That is, until last year, when my brother-in-law suddenly passed away. To get through this loss, I began editing the Wake Up, Maggie! manuscript again. After being turned down by another small press, I pitched it to my publisher, a lifelong diarist, who fell in love with our project. Wake Up, Maggie! Go Away, Mom! A Memoir in Two Voices had finally found the right home. I realized, after all these years, 24 in all, that not only was persistence the path to publication, but when combined with a creative venture, it also had the power to heal the most important relationship in my life.

___

Carol Weis is the author of the memoir, Stumbling Home: Life Before and After That Last Drink, the Simon & Schuster children’s book, When the Cows Got Loose, and the poetry chapbook, Divorce Papers. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, AARP, Cosmo, the Independent, Salon, ESPN, Ravishly, GH, Today’s Parent, Literary Mama, Guideposts, and numerous other outlets, and has been read as commentary on NPR. A single Mom for 13 years, Carol is a Jersey girl who lives in Massachusetts, close to her grand kitties. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Meet Me in the Middle: Reflections on 33,000 Words

June 11, 2024 § 19 Comments

By Allison Kirkland

As a teenager I lulled myself to sleep with fantasies of a literary life. Lying in my white four-poster bed, I’d stare at the ceiling and imagine myself other places:

On glamorous vacations with other writers, feeling like part of the club.

Giving keynote speeches at universities, followed by parties with free-flowing wine and copious cheeses.

Being told I was genius, that I’d written a great American work of art, that I’d changed the world.

Back to reality: In 2023 I began sharing an office at a co-working space Mondays and Thursdays, which means that for the past year, those are my writing days.

So on Mondays and Thursdays I stuff my laptop and my lunch in my backpack and grab a piece of chocolate if I can find one. I drive to my co-working space, open the door to my office, set out my laptop. Hearing that office door shut behind me cranks my brain on—suddenly, I’m back in the manuscript. I write new words. I erase some of them. I build new paragraphs, and sometimes re-arrange them. I get up to stretch. I break for lunch.

I write for an hour; longer if I can squeeze it in and the words are flowing. It’s an absolute luxury—two full mornings to write, every week. It’s also a lot of solitary work, a far cry from the literary parties and conferences that I imagined as a teenager. Forget changing the world; I’m barely in the world these days! Just me and a computer, week after week, showing up and doing the work.

First I wrote 100 words in that little office, then I wrote 1,000 words. Soon I’d written 5,000 words. Then 15,000. I watched the word count climb. 20,000 words. Bird by bird, as Anne Lamott so famously says.

This month I hit a milestone: 33,000 words. Most memoirs average 60,000-75,000 words, so I’ve hit the halfway mark, more or less.

***

About a year into this process I saw a tweet that haunted me: Your writing might not change the world but it will change you and that’s enough.

No! — was my first thought. I have to change the world. That belief had sustained me through pages and pages I’d crafted alone every single week for the past year.

If I wasn’t going to change the world, what were those hours worth? I’d been sitting alone in my office, tangling with old memories, blowing off friends and being the opposite of who I’d been for many years: someone who didn’t take her own work that seriously. If I didn’t change the discourse, and change the minds of millions, why was I even writing?

I screenshotted the tweet. I wanted to remember it, to see if it was true. It seemed like something people would say to make themselves feel better when their original dreams didn’t pan out.

Now, looking over my 33,000 words, I have another thought: Why was I valuing everyone else above myself? Did I matter so little?

***

When I started this memoir, I had a million ideas for what the finished book would look like. I wanted it to say a certain thing about what it means to be human. To be done by a certain time. To be acquired by a certain publishing company, with a certain agent.

I had a million ideas for how this book might change the world: it would show people that ableism was real, it would right some wrongs, it would become a part of the canon of disability writing.

And I hold these desires close to my heart, because marginalized people write to take back power where they’ve had little; to light a path for others who’ve had similar experiences.

But here’s what I’m left with now: all of this thinking, and still I hadn’t given any thought to what I might look like when the book was finished.

I am not the same person even halfway through this manuscript, and I still have miles to go.

I didn’t start writing this memoir for personal growth. That seemed like the opposite of literary. I wanted recognition, the opportunity to change the world.

You can roll your eyes when I tell you that I’ve gotten so much more. I’ve found delight and confidence in learning to put my experience down on paper. I’ve found satisfaction in seeing the work grow. I’ve found compassion for my younger self, a better understanding of choices I made in the past that didn’t make sense to me at the time. I’ve found that I am not who I thought I was: I’m someone who takes her work seriously. I’m someone who can delay gratification. I am someone who belongs.

It’s true what they say—the work we make, remakes us.

And I guess I still want to change the world a little bit. Because I can’t stop thinking about the kind of world we might create if everybody knew they were worthy of taking Monday and Thursday mornings to put their life down on paper—just for themselves.

________

Allison Kirkland holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from The New School and leads writing workshops online and in Durham, North Carolina. Her publications include personal essays, interviews and arts journalism, and her work has received support from the Norman Mailer Center and the North Carolina Arts Council. Subscribe to her Substack about creativity and the writing life, the intangibles.

Blind Optimism is Better Than None at All

June 10, 2024 § 10 Comments

By Dana Shavin

I have been struggling to write the same story for three weeks. About a week in, I thought it was finished, so I sent the seventeen-page behemoth off to my trusty writing mentor, thinking she would respond with high praise and a directive to submit it instantly to the most prestigious journal I could find. This is not what happened. This is not even close to what happened.

So I worked on it for another week. There’s a well-known joke that circulates among writers, that when asked how his writing was going, Oscar Wilde said, “I spent all morning putting a comma in and all afternoon taking it out.” That’s pretty much what I was doing, only at the level of the paragraph. But one night at dinner I thought I had a breakthrough. I was very excited, and the next morning I raced to the computer to slam out what I was certain would be a final, stellar draft. This is not what happened.

After several more days, still at a loss for how to proceed, I texted my trusty mentor and asked if she could talk me off the ledge. I estimated it would only take about fifteen minutes, not because the ledge wasn’t super high or terribly narrow, which it was, or because the fingers with which I was I was clinging to it weren’t wet with the sweat of angst and torment, they were, but because if anyone can move me off a scary psychic ledge quickly, it’s her (my husband too, but he was playing golf). She agreed to talk, and for a while afterward, I felt calmer. I thought I’d put the agitation and pessimism behind me and that I would soon move forward again on the story. This is not what happened.

At some point during the alternating states of rewriting and announcing (silently, to myself) that I was never writing again, my mentor emailed to remind me about what Albert Einstein said, that problems cannot be solved by the same consciousness that created them. I loved this. I decided I needed to find a new entry point into my tale, maybe even needed to rethink what my tale was about. Maybe I was stuck because I kept trying to tell the same story the same way, only with different words!

I went to bed believing that my unconscious would solve the riddle of the wayward story. What actually happened was I had a dream about a school bus race in which all the drivers were St. Bernard dogs. I tried to interpret the dream in light of my problem of stuckness—perhaps the school buses were my educated mind, and it was racing to get to the finish line with an intrepid, but ultimately unqualified, driver at the helm—but this did not move me forward. Plus, I now truly despised writing and wanted to try my hand at something less taxing and obtuse, like cryptographic arithmetic or particulate chemistry.

So I took Einstein’s advice (again) and took a walk with the dogs while gently cradling my story in my unconscious like a baby, or a small, hot sun (both of which I know never to look at directly). Then I went to the market, after which I plundered some old letters looking for I didn’t know what. I found one from 1990 from my old college friend Jack in which he told me he was going to be a dad, which was sweet and nostalgic, but it did not move me forward on my story. Nor did eating chocolate, checking Facebook, watching the squirrels gymnastic through the treetop canopies outside my office window, playing hours upon hours of pickleball, cooking, napping, reading, drinking wine or staring expectantly into the computer screen holding my mouth just so.

While I am still stuck as of now, I love the idea of my unconscious being a sophisticated piece of machinery that can both download a puzzle and upload its solution. I also love the idea that somewhere in the school bus of my mind, there is an able driver just waiting to take over the wheel. Mixed metaphors aside, my trusty mentor has advised me not to be in a hurry to figure the story out.

“These things take as long as they take,” she is fond of saying.

And then there’s Einstein again, who claimed that failure is success in progress. It’s with that optimistic notion in mind that I conjure the actor Charlie Sheen, who famously said, as his star was crashing, “Winning!”

Which was not at all what was happening. But it’s better to have blind optimism, I suppose, than no optimism at all.

Originally published in the Chattanooga Times Free Press (where Dana is a humor columnist) in May, 2022.

___

Dana Shavin’s essays have appeared in Oxford American, Psychology Today, The Sun, Bark, The Writer, Fourth Genre, Parade.com, and others. She is a national award-winning columnist for the Chattanooga Times Free Press and her memoir, The Body Tourist, about the intersection of her anorexia with her mental health career, was published in 2014. Find a complete list of publications at her website.

Left-Brain Right-Brain: A CPA Turns to Creative Writing, With His Dad’s Approval

June 6, 2024 § 16 Comments

By Brian A. Rendell

After thirty years of building a financial career, I did what any self-reflective CPA would do – begin an MFA and focus on creative writing.

Huh?

Twenty years ago, a career coach suggested I take a personality test to discern why my professional career wasn’t satisfying. The results revealed my left and right brain functioning were relatively equal, 54% left-brained (logic, facts, and math) and 46% right-brained (imagination, creativity, and rhythm).

I call my left brain, logic brain (“LB”) while right brain is rhythmic brain (“RB”).

My coach said, “You’ve focused too much on analytical LB actions and ignored creative RB activities.”

Upon hearing this diagnosis, both sides of my brain had strong opinions.

RB: Cool! We should be having more fun!

LB: Nonsense, get back to work.

Since LB was slightly dominant, I went back to climbing the corporate ladder. It was my dad who influenced me to pursue a safe, stable LB profession like finance. Born in 1930, he valued stability. After forty years of shiftwork at the mill, he wanted more for me. I was the kid who did what was expected of him, always wanting to please.

I still am.

Eighteen months ago, while LB was distracted trying to solve an inconsequential problem – something to do with matching my belt and monk strap shoes – RB saw a post about a low-residency creative writing MFA program. Intrigued, I signed up for an information session. I loved what I heard – learn the craft and publishing skills to produce the novel welling up inside you – but doubted whether I had the skills, or the guts, to enter this creative world.

LB reminded me, “You’re not a journalist, academic, or English major and haven’t spent your life with a book in hand.” The truth hurt. What if I failed in this RB pursuit? It would be humiliating.

RB said, “Take a chance and enjoy yourself! Life can be short.”

My mother passed away twenty-seven years ago at 58, not much older than I am now. My closest childhood friend died recently at 54.

Dad will soon be 94, has mild dementia and is quickly losing his short-term memory due to Alzheimer’s. His long-term memory, however, is intact. He’s always been a storyteller, something I inherited.

The stories start with my grandfather leaving a meagre subsistence on Fogo Island and journeying to a new company town in 1908. The Englishmen who created the town paid him an ungodly $1.43 per day. When he informed his mother, she slapped him across the face and said, “Don’t you lie to your mother! Nobody makes that kind of money!” Later, on medical leave in London during WWI, he learned his employer had been topping up his wages during the war. And what did this young man do with this newfound cash? Have a suit tailor-made and sit for a portrait!

I have that portrait hanging in my home office today. I felt a magnetic force pulling me to write a manuscript based on Dad’s stories, and I don’t have a lot of time to capture Dad’s memories and for him to enjoy my work.

Once again, Dad was nudging and shaping my career path.

But could I really do it? Did I belong in this RB world? The university’s MFA leader suggested I begin writing in earnest and see what happened.

I allowed myself to begin writing, too embarrassed to tell those close to me. Then words started flowing and wouldn’t stop. Soon, I was waking early on weekend mornings excited to write and waking in the middle of the night with ideas.

I applied to the MFA program and held my breath. The evening I learned I had been accepted, I hardly slept. My mind was racing about my story and the reality of what joining the program would mean. I would need to devote at least twenty hours each week to the MFA and my manuscript. I didn’t think I could do the MFA and maintain my 50 hour/week career; I began investigating early retirement. With the support of my spouse, I took the big leap, three years earlier than planned.

It was the most excited I’d felt in years.

I’m now in the last year of my degree and recently hit the midpoint of my draft manuscript. On social media I’ve changed my title from “financial executive” to “writer.”

LB is dazed and confused. RB has a new swagger.

When I remind Dad that I’ve retired to write about our family stories, he lights up. I hope the first draft is complete in time for him to be cognizant of what I’ve done. Maybe I’ll go home to Newfoundland to read it to him. Whatever happens, I’ll know his stories are captured.

LB has served me well over the past 30 years, but it’s time he buckled-up safely in the back seat. RB is behind the wheel and Dad is riding shotgun. The road ahead is curvy, bumpy, and unclear.

The new me is smiling.

_______

Brian A. Rendell is a Canadian writer writing historical fiction set in his home province of Newfoundland & Labrador and London, England. He recently returned from the British Library archives where he found intriguing details about the founder of his hometown, Lord Alfred Northcliffe and his wife Lady Northcliffe. Brian was thrilled when a NYC agent told him his story reminded her of Julian Fellowes’ HBO series, The Gilded Age. He is in his second and final year of a MFA at the University of Kings College in Halifax, Nova Scotia and is determined to have his manuscript’s first draft completed next year.

When You Can’t Write: Collage, Craft, Create

May 31, 2024 § 9 Comments

By Yvette J. Green

Recently, having finished my manuscript and starting the submission process, I felt lost. There were no images with Joan Didion shimmers around them propelling me towards my notebook. I sat at my desk and sifted through memories, hoping one would step forward and connect itself to the present. I thumbed through my thoughts, but no intense emotions requested interrogation. So I veered somewhere outside of my head, to an arts workshop sponsored by The Phillips Collection, an arts museum in Washington, D.C.

After the facilitator, Brittany Monae, shared introductory slides, discussed the layering aspect of collage, and displayed some of her own work that included pieces of wood, I was inspired. Magazines, scissors, and glue provided by the museum were already on the table in front of me. I ripped out pages splashed with seafoam, succulents, and forest greens. I embraced the land and the sea. Giraffes in the savanna stood gracefully. Communion was visible through a picture of a brown-skinned man kneeling beside a rhinoceros lying on his side. The two were engaged in a tête-à-tête as the man rested his head on the animal’s face just above its horns.

I went to the back of the room to rifle through containers of decorative accessories. I gathered brown, teal, and purple buttons, navy and layered fabric of maroons and purples in the sliver of space I had carved out in front of me. When I was ready to make my final choices, I did not overthink. An image of four women spoke sisterhood. Deep purple fabric remnants emblazoned with gold stars were luxurious. Light hitting a faraway sunset gave way to blushes and lilacs. The single cerulean butterfly in the magazine page complemented tangerine wings on the opposite page.

My arm and hand curved to follow the line of the image I excised. The kinesthetic outlet provided me with needed singular focus. I peered at the line, where it turned, and changed course. The pictures on the slick paper that distracted from the focal object were expunged.

Scraps hit the floor.

I was consumed.

For those short minutes, my eye was in charge. Lack of skill and talent were not deterrents. Harmful thoughts were on sabbatical.

I did not need to syntax words on the page for a project, nor in the air to guard someone’s feelings. I did not worry about gerunds or passive voice.

As I prepared to memorialize the moment, I was sure Elmer’s glue would fail to adhere my fabric to the craft board.

“You should use a hot glue gun to be sure that the fabric stays put,” the artist suggested.

Sure I had one at home, I mentally searched drawers and cabinets while cutting out my next image.

“You can temporarily use the glue stick. Or wait. This is for you. Don’t rush it.”

I slowed down even further, discarding images that no longer cohered with the feeling that was emerging.

I needed to finish at home. There, I found my glue gun and sticks. I also found Mardi Gras beads and doubloons, accumulated over the last three years when my college friend sent me king cakes that my sons and I quickly demolished. The purple, green, and gold beads reminded me of my friend’s love, college days, and my family.

I found Jean-Michel Basquiat cards. Shimmery violet butterflies floating against a fuchsia background were the last images I needed.

The four women I had saved from a lifetime of enclosure between covers at the back of a storage room were braiding. Two women sat on the floor, each separating the extensions to hand to her braider. The braiders sat in plastic chairs behind the women whose hair they were braiding. I had something new to fixate on: the communal act, sisterhood, and care.

***

“When we create art we are doing so in the moment. With every brush stroke, every choice of color, texture, and use of materials, we are in the present moment,” writes Wendy Meg Siegel. When writing is not working, choose a different medium to return you to the present, to quell your anxious mind.

The process of cutting images from a larger piece and letting remnants fall to the floor can be meditative. Cutting can be a kinesthetic outlet. Letting unneeded remnants fall to the floor can be literal bits of paper, intrusive thoughts, or ideas that lack energy and are taking up space blocking the way for new ideas to enter in.

Gathering knickknacks and miscellany from around your space can help you focus; a mental feng-shui clearing cobwebs and creating new energy.

Revisiting old memories or journals tucked in storage cabinets might offer a secret passageway back to the page.

Choosing images that delight the eye, instead of fretting over a precise synonym or an aggressive verb, can thwart our war with words.

Let your eye lead you. Participate in another art form where the stakes remain low. Will this new venture immediately yield words for you to arrange on the page? The Magic 8 Ball of our youth says, “The possibility is great.”

Yet, you may not need to return to the page just yet.

Collaging provides an aperture to see differently. To gather. To create connections. To create your own viewfinder. The collage can fill you with joy. Or give you space to be present. And rest.

***

A Southern girl from Nashville, Yvette J. Green holds a BA in English from Xavier University and an MA from the University of Maryland, College Park. She is an alum of Tin House’s Winter Workshop and a Periplus Collective Finalist. Yvette’s writing can be found in Salon, Slate, Viator, midnight & indigo, 45th Parallel, among others. Find out more at yvettejgreen.com.

Should Writers Ever Look at the Comments Section?

June 7, 2024 § 5 Comments

By Samantha Ladwig

“Do you ever read the comments?” I’m always asked – usually towards the end of a session – when I teach a workshop on pitching.

For a long time, I said, “No, and you shouldn’t either.”

My experience with comments is that, if I’m not prepared for the negative ones, looking at them at all, even if they’re overwhelmingly positive, sucks the initial excitement out of the otherwise pleasurable experience: an editor accepting a draft, taking and shaping it into something I’m even prouder of, and scheduling it for publication.

I approach my essay’s “live” date as the day it stops being mine and starts being the readers (if anyone is interested, of course).

But I’m not immune to my own curiosity, so occasionally I break my own rule and have a peek.

I recently published an essay with Literary Hub about my experience buying and running a bookstore at age 29, in the county with the highest ratio of senior citizens in Washington State. It’s a piece I’m proud of, that I felt I needed to write, but one that I was nervous to see out in the world because it dealt with my own community.

The morning it went live, I let those nerves steer me, unthinkingly, towards the comment section. Per usual, on a site that receives a mixed bag of intentional readers and anonymous trolls, the first commenter wasn’t a fan. In just one second, after hours spent working on an essay that came to me two years before I was able to write it, the joy of seeing it in the world vanished. I spent the day kicking myself for not pausing before clicking open that essay’s comments section.

When I’m asked whether I look at the comments, my impulse is to say no because I want to spare my workshop students the distraction of that experience. The approval to lean into, especially in the beginning when emotions are high, should come from the editors who’ve selected and molded the essay for their publication, not random readers inhabiting a space often open to anyone, anonymous or otherwise, good intentions or bad.

The students who ask me whether I read comments do so in hushed tones, as if my confessing that “yes, sometimes I do” is admitting that I’m not as good a writer as they want me to be, or the kind of writer they aspire to be, someone so confident in their craft that they don’t need anyone’s approval.

Maybe the question isn’t whether I look at the comments, but rather have I risen above creative anxiety. I don’t know anyone who has.

It’s natural to want your writing to connect with a reader. And it’s natural to fear that it never will.

I’ve been writing professionally for a decade now and have witnessed a full spectrum of reactions. My writing on family estrangement went viral, receiving thousands of comments and reshares with one person going as far to say that it was the only Vice article they’ve read that wasn’t followed by a barrage of hatred. On the opposite end of the good/bad spectrum, as a movie critic for a male-dominated outlet, my mediocre review of the 2016 Warner Bros. animated film Storks upset readers so much that they took it to Reddit where I watched enraged men talk about me in unsettling ways.

Rarely does a work elicit these extreme responses. A lot of the time it’s some nameless person jumping between essays, telling people they used an apostrophe incorrectly.

There are wonderful comment sections out there. The Brevity Blog, for instance, has an engaged community made up of writers who enjoy reading about their craft. Substack is another excellent resource that lends itself to meaningful connection between author and reader. It’s not that everyone is fawning over the work, it’s that the commentary is deliberate. That makes all the difference.

Now, when students ask that question, I’m more transparent. I tell them it depends on the work, the publication, my emotional state. “I try not to,” I say, “but sometimes I do.”

___

Samantha Ladwig’s writing has been published by The Cut, Vulture, Literary Hub, Vice, Real Simple, Bustle, The Brevity Blog, and elsewhere. She reviews books for BUST magazine and co-owns Imprint Bookstore in Port Townsend, Washington. Find her at samanthaladwig.com

Share this: