Words, Words, Words

November 30, 2022 § 13 Comments

By Marcia Yudkin

During one of my entrepreneurial projects, I stood in a recording studio at Berklee College in Boston performing a script I’d written on increasing one’s vocabulary. Another woman and I took turns saying each word, defining it, then illustrating it in a sentence. During a break, the other woman turned to me and commented, “You really feel words, don’t you?”

I looked at her. Did I?

Euphonious: nice-sounding. The salesman disarmed me by speaking in euphonious tones.

In elementary school, tinkering with words was as natural for me as other kids playing with trucks or dolls. An aunt gave me a hardcover anthology of poems for children, and I was hooked. The sound of words and ways they could rhyme captivated me. I would read verses from The Golden Treasury of Poetry out loud and in a wire-bound notebook scribble stanzas of my own. At age seven, I read two of my creations on a local TV show, swinging into the echoes of “know” with “snow,” of “spring” with “king.” That aural resonance was the thing

Flaunt: display flagrantly. Though he had so much he could never spend it all, Richie Rich tried not to flaunt his wealth.

From the enchanting sound of words, I moved on to their meaning. With my weekly allowance I bought a paperback called 30 Days to a More Powerful Vocabulary. It cost 35 cents. Before going to sleep, I studied it, learning words like “ascetic,” “querulous” and “vindictive.” I especially devoured a chapter called “Words for Mature Minds” containing words that the author, Wilfred Funk, said nine-year-olds would not be able to understand.

Not long afterwards I injected one of those words—“maudlin”—into a composition for my third-grade class. “You see, I was not the maudlin type,” I wrote, noting how surprised I was that other kids cried their first day of school. “So there, Dr. Funk!” I thought with great satisfaction (although my use of “maudlin” was a bit off kilter).

Apotheosis: culmination or highest point. Marilyn Monroe was the apotheosis of Hollywood glamour.

Words also gathered associations. Today I can’t hear the word “obstreperous” without thinking of my grandfather. Self-educated because he’d had to leave school at 13, he read mysteries and histories in a high-backed wing chair in our living room, tapping the lit tip of his Havana cigar into a beanbag ashtray. Even when we kids behaved well, he called us obstreperous, I think because he enjoyed having that complicated a word roll off his tongue.

Since I too read like a fiend, I collected phrases from books that stuck word for word in my memory. This might consist of a bombastic nonfiction title, like What You Should Know About Communism and Why, or a snappy line from Catcher in the Rye, such as “If you want to stay alive, you have to say that stuff.” And as a grownup, I felt thrilled when I was able to insert—appropriately, wryly—Jane Eyre’s “Reader, I married him” into one of my books. With just four words I could breathe a puff of Charlotte Bronte’s passionate intensity into the tale of my own clandestine romance.

Visceral: felt immediately in the gut. Her opponent’s insult had a visceral impact on the governor.

As my Berklee College script-reading partner had intuited, for me words have one more element. Besides sound, meanings and associations, they have oomph. Words can shoot out of you like pellets of energy or at you like a baseball hitting your solar plexus. “Obstreperous” has oomph. So does “albondigas,” a punchy word from my seventh-grade Spanish class that I loved so much I would say it again and again with exaggerated vigor. (It means “meatballs.”)

Sometimes the oomph is personal. I spent a year working in China at a time when outsiders stood out. When I traveled, kids would run after me and my blond companion, gleefully shouting “Waiguo ren!” (“Foreigners!”). When I rode the bus in Beijing, adults would stare. After eleven months of this, a five- or six-year-old boy leaped into the air with “Waiguo ren!” when he saw me, flicking a switch I didn’t know I had. Without thinking, I stalked toward the boy. Just as quickly, the boy’s father stepped in front of his son. “He’s welcoming you, you see,” he said in Chinese, giving me a worried look.

Catharsis: emotional release. After so much struggle and pain, the funeral represented a catharsis for the poor man’s family.

Ah, words. In any language, they dance, sing, point and sometimes sting.

__________________

Marcia Yudkin lives in the woods of Goshen, Massachusetts. The author of 17 books, she publishes a Substack newsletter called Introvert UpThink, in which she critiques society’s myths and misunderstandings about introverts. In addition to her newsletter, you can follow her on Twitter.

In Praise of One Beat Words

May 18, 2022 § 24 Comments

By Linda Button

Here’s to one beat words. Short and sweet and quick. Hot in your mouth, fast to say, they leap from tongue to brain in a flash. They amp up your tone and add salt to your prose. And by one beat words I mean short.

Short words are honed to work fast. Why? Most hail from the harsh north, where each breath is hard won. Blunt like chipped tools. Tough to make it through dark, cold nights. Not like the tongues from the warm south, born of sun filled days, where time stretched out with ease, no rush! and each sound led us down a long, slow path that seemed to have no end.

Words from the north cut to the chase. (A phrase, by the way, from the first days of film, where they meant “cut to the good stuff)”.

My folks, spawn of a long line of hicks, spoke in grunts. Dogs were mutts. You swam in the crick. Fixed the ruf. Each word shot from my dad’s mouth. We paid close heed. We ducked and did what he said. “Git here.” “Go on.”

Then, I was wooed by a posh school. They did not teach me to write well. They loved such long words. Lots of them. Scores. Tomes. Why use three words when you could use twelve? Fill the page, they pressed us. We purged our guts, plied words from our word gods, stuffed our work to awe our profs. Big blocks of text. No white space. No sense of dire. All was flat. We thought that made us sound, not just smart, cool.

But

where

were

our

crisp

bold

thoughts?

Lost in veils. We had draped them in fluff. Masked and dressed for show.

I learned how to write when I got my dream job in, well, we called it the boob tube. The boob tube. Fourth grade zone. True. We learned to keep it short to reach the most folks. Our goal: keep them glued. “How much time do you have? Wait, wait, don’t go! Stay here. Look, here’s a new fun thing we just found for you. Try this. Try that. Stay with us.”

We wrote scripts for the ear, not the eye. That taught me to be blunt, like my dad. Hack off the dreck. Cut to the core. Clean up your prose. Trim the split ends. We carved each plea to one beat. We got to the point. We caught them in our trap.

Wow, I thought. I can say less and mean more.

Try this

Fill a page with your tale. The whole side. Then, take each word: the four beat, three beat even and, yes, the two beat words. Find a way to say the same thing with one beat. See how you forge a clear stone path of thoughts to the end. See how they change the pace, how the quick steps fuel what you mean.

Our brains eat short words like fast food. That makes sense. Short takes less space. Each word drops in, plunk.

Then, when the time feels right, slip them one glorious note.

Glo-ri-ous. Mmmmm. Stands out, right?

Choose your words with care. Hone them. Make them punch through.

And, please, keep it short. And glorious.

In this blog I have used just one beat words. Tell me, did it work, or am I full of bunk?

_____

Linda Button spent 20 years running an award-winning agency and romping across six continents to speak on creativity and writing. Her essays on relationships have appeared in the New York Times Modern Love and Boston Magazine. She completed the Memoir Incubator at Grub Street and is working on a memoir about marriage, madness, and how martial arts saved her. https://lindabutton.works

Discovering Your Genre: Prose, Poetry, or In Between

March 15, 2022 § 4 Comments

How does a writer who works in both poetry and prose, or on the cusp of both, decide which genre best expresses a particular subject? We, Ann de Forest and Amy Beth Sisson, are critique partners for poetry but we both write prose as well. In conversations about our experiences, we posed this question. Here, we explore some differences between the genres and offer experiments and exercises to help us – and other writers – decide.

From Prose to Poetry

Ann: I came to writing poetry late. In writing prose, I was often drawn to hybrid forms like lists and collage. A project of essays on churches in Rome eluded me. I felt forced to interpret my experience and draw conclusions. Reconceiving the essays as poems released that pressure. Compressing my experiences into poetic stanzas, I found, embodied perfectly the feeling of moving through a church’s interior spaces. Spiraling into the experience, I could invite readers to float along with me, free to have their own interpretations.

Amy and Ann: Together, we considered the energy that poetry brings to the material. A poem can be a compression, abridgement, or distillation. Lorine Niedecker, in her poem, “Poet’s work” uses the wonderful word “condensery.” Finding the poetic in prose, sometimes by a process of erasure, can transform the prosaic and instill unexpected power.

Poet Gregory Pardlo, whose poems compress autobiography, history, racial injustice, pop culture, and philosophy – rich themes often explored in essays – named one collection Digest, which rings just right. Digest carries lovely multiple meanings: a compilation of material, a simplification of information, as well as the biological processing of nourishment.

A poem moves by spiraling inward, even a poem that leaps back and forth, or flings out a range of images lands on a still point. A poem exists as a single entity that stops the reader in time, while prose compels the reader to move forward, to turn the page.

Kazim Ali, in writing the same material in both poetry and prose, illuminates the differences. In his 2017 poem Origin Story, he writes, “Someone always asks me ‘where are you from’/And I want to say a body is a body of matter flung.” In his 2021 nonfiction book Northern Light, he revisits this: “I’ve always had a hard time answering the question “Where are you from?” The easiest answer—the one I’ve fallen back on as a convenience, though I had always supposed it to be as true an answer as any—is that I am “from” nowhere.” His different linguistic choices are striking. In the poem, the music of the meter, of the word “body” repeated, the alliteration and near rhyme of “from” and “flung” incise meaning into the ear as much as the mind. His prose is more straightforward, more conversational, though no less artful: the paradox of being from “nowhere” packs a punch.

From Poetry to Prose

Amy Beth: I went through the reverse journey from poetry to prose when working on a project writing poems based on archival material from my town, Swarthmore, PA. I drafted a poem on a complex issue of segregated housing but couldn’t make it work. I allowed my draft to burst the bonds of a poem, free associated, and expanded the material into a lyric essay that ranges from companion planting in gardening to the history of the use of guinea pigs.

Amy and Ann: We delved into the expansive nature of prose, particularly the lyric essay. This form fuses poetic and narrative techniques. A lyric essay may be a braid (multiple ideas threaded together) a collage (a juxtaposition or layer of ideas), and it can be nonlinear (breaking a chronological narrative.) The lyric essay leaves room for the reader to co-create. It is a spiraling out in theme, time, and place. It doesn’t land on a single spot.

Poet Julie Carr spoke about why she chose prose for her upcoming nonfiction book, Mud, Blood, and Ghosts, which draws on an extensive family archive. “There never could be poems from this. Writing poems is about present time. To be a body in the present. To write about past and future is to write essay.” Then she added a retraction of sorts: “Whenever you make these distinctions they fall apart.” We could relate to that!

Exercises:

How to decide which form best suits the project you have in mind? Allow yourself to experiment with both genres. Start with something you’ve drafted in one form and convert it, at least temporarily, to another. You may end up with a poem, an essay or something in between (prose poem or flash)!

For turning an essay into a poem:

Think of the game Jenga. Your prose is like a stable tower of blocks. To make it a poem, start pulling out blocks. How much can you remove and keep the tower aloft?

Some tips:

- Find the core image/idea

- Find sonic, rhythmic, visual links

- Compress/Condense

- Remove transitions and other superfluity

For turning a poem into an essay:

Think of the folktale Stone Soup. Open the cupboard of your mind and start throwing ingredients into the pot. Experiment (some ingredients might surprise you). Keep adding until they cook together into a new nutritious stew.

Some tips:

- Explore the long trail of your images and ideas.

- Invite the reader along on your explorations

- Expand time in both directions — past and future

- Welcome the unexpected

Approach the question in the spirit of play and discovery. You can always veer back or off into a new direction. As poet and essayist Marianne Boruch said, “Both poetry and the essay come from the same impulse — to think about something and at the same time, see it closely, carefully, and enact it.”

____

Whether poetry or prose, Ann de Forest’s work often centers on the resonance of place. Her short stories, essays, and poetry have appeared in Coal Hill Review, Unbroken, Noctua Review, Cleaver Magazine, Found Poetry Review, The Journal, Hotel Amerika, Timber Creek Review, Open City, and PIF, and in Hidden City Philadelphia, where she is a contributing writer. Ways of Walking, an anthology of essays she edited, will be published by New Door Books in May 2022.

Amy Beth Sisson is struggling to emerge, toad-like, from the mud in a small town outside of Philly. Her poetry has appeared in Cleaver Magazine and The Night Heron Barks. Her fiction has appeared in The Best Short Stories of Philadelphia 2021, Enchanted Conversation and Sweet Tree Review. This fall, she left her day job in software development and started an MFA in Poetry at Rutgers Camden. You can follow her work at amybethsisson.com

We Write to Taste Life Twice

May 20, 2020 § 10 Comments

By Anna Rumin

By Anna Rumin

For the past five years I have been designing and teaching memoir-based writing courses at our local university. Once a week, for a period of five weeks, participants arrive with a memoir based story that they have prepared to share with the group. During the week, they commit to writing for 15-20 minutes a day using prompts.

Writing is a lot like anything else – the more you do it, the stronger and more comfortable you become as a writer. In the final week, participants arrive with a story of up to 1000 words that they want to share with friends or family or a publication – it is the one and only class in which I ask them to think about giving and sharing their story as a gift, as a piece of writing that plays tribute to what we don’t want to forget.

My focus as a teacher is to give the participants enough prompts and enough writing exercises that they are never without a story to write. And let me assure you, that almost every single participant who has sat around that table has had a story that we have carried with us long after the class is over.

We write to taste life twice ~ Anais Nin

We’re cocooning now. If you have a quiet place to write, be it on paper or on a computer, you too can begin recording and collecting the stories from your life. To get you going here are some prompts – remember, write with abandon, don’t stop to edit and don’t overthink anything.

- Make a list of the things you have learned to do: tie your shoes, dive, break into a car, drive standard while smoking a cigarette and drinking a coffee, milk a cow, ski, bake a cake, play the violin, build an outhouse, ice-fish, make bread, make wine, make beer, speak a third language, sew, knot pearls, build a stair-case, sail, skin a fish, catch a fish, train a dog, train a toddler, pluck a chicken, get along with an in-law – now write the story.

- How about all the stuff in your house that has a story but nobody wants? Take photos of the teeth-marks on the dining room table, the Royal Doulton figurines your mother collected, the paintings your great Aunt Margaret gave you, the stamp collection left to you by your grandfather, the maroon velvet footstool found in the attic of your house, the collection of beer bottles, the old clock… What is the story of that table and who has sat around it, and what are its happiest memories? Write the story – and even if nobody wants that old table, tell the story of what you know from having kept it for so long.

- How about your clothes and jewelry? Tell us about your scarf collection and why you have so many shoes and why you insist on keeping that damn bathrobe? What are the stories hidden there?

- Put a photo of your mother in front of you. Make a list of the things your mother held in her hands – choose one thing each day from the list and write the story. Do the same for your father, for yourself.

- What animals have played a role in your life? What do you know from having had a pet that you didn’t know before? What do you know from having watched wild animals – write about that raccoon you found hiding under the kitchen sink, the fox that waited outside your door, the crows that wake you up every moving.

- Where and from whom did you hide when you were little? When were you most scared? Most excited? Most in love?

- Have a look at your library – the one you have and had – what are the books that have played a role in our life?

- Make a list of strangers you have encountered. Now write the story.

- Look out the window, go down memory lane and write about the first time your heart was broken.

- Look out another window, go down memory lane and write about the first time you experienced loss.

The key is to recognize that even the smallest of things can carry huge stories; things like the stuffed animal you still have, the letters from your first love, and the wooden spoon your grandmother used to stir the applesauce in the years before she forgot what applesauce was. If you’re cocooning and thinking about writing, just start and remember: keep everything, honour every single story you write. And remember to pay attention to the stories that you want to give as gifts – gifts that you created during that time Mother Nature demanded us all to cocoon.

___

Anna Rumin is a native Montrealer whose identity has been shaped by the political landscape of her home province, her Russian roots, a passion for life-long learning that has been woven both formally in academia and informally through travel, voracious reading and writing, and a love for the stories hidden in our natural world. Her interest in narrative inquiry stems from her belief that not only do we all have a story to tell, but that our stories help us to better understand who we were, who we are and who we are becoming. She has now designed twelve memoir-based writing courses that invite participants to think of themselves as the narrators of their life as seen and written through a particular lens. Regardless of who she is working with, Anna is committed to supporting those she leads, by providing them with opportunities to set and meet their goals. In her spare time Anna writes short fiction and has been the recipient of numerous awards.

Taking Flight Through Writing Prompts

April 24, 2020 § 17 Comments

By Jan Priddy

By Jan Priddy

Unlike a bird that finds safety perched while asleep, human beings have no physical locking tendons to hold us still.

In a recent Brevity blog post, Grace Segran describes “freezing up” the first time she was given an in-class writing prompt. The idea of such writing, Segran writes, “Makes total sense. Theoretically. In practice it appears that for many of us, nothing much comes out of it.”

As a public high school teacher and college adjunct I regularly gave writing assignments to all students. They wrote about their most peaceful places and reader-responses to essays set in front of them. They wrote to in-class prompts off the top of the heads and counted words written in ten minutes. They wrote complete stories of 225-275 words, one each week for most of a term. They wrote essays in MLA format and explored arbitrary revision strategies such as cutting the last lyric paragraph and moving it to the beginning, cutting five words from a paragraph, five more, and then half the total number of words. I insisted they do it. It’s the reason John Rember claims teaching is an act of aggression. I made them buy that dress.

No one likes to be forced to do anything, and even I hate being compelled to write, so I get that. On the other hand, nearly every piece of writing I have published came from an assignment or prompt. Each year, I completed the essays and stories I assigned to my students. Much of that writing started right in class with all of our heads bent over journals. Writing under pressure? Revising sometimes only because the instructor will check to be sure it’s done? Because I feel I must? Deadlines? That’s the way it goes. Writing responds to something, in conversation with experience or with ideas.

Early in the year we drafted a satirical “pet peeve” essay entirely in class, one paragraph in twenty minutes each day for a week. Strict guidelines, that is: prompts. Later we added sources, went to the lab and typed, peer edited, and revised. I did not read their early drafts unless they insisted. The completed humorous essays were twelve hundred to two thousand words and modeled a strategy for breaking down a complex task into manageable pieces. We did this assignment in October and even by June’s anonymous assessment, it remained one of their favorites.

My students wrote to assigned, boring prompts in order to get into college. They wrote essays and stories they would not have chosen merely because they wanted to pass a class. Sometimes they took the prompt home, but often they had to complete the first draft in front of me. They didn’t always like what I made them do. They complied because I pushed hard. And eventually most of them noticed how it helped. Moving their conclusion improved both beginning and ending. Cutting words made their essay stronger. The rules of MLA are predictable and allow ideas to shine. A few of them went on to gain MFAs in writing or tenured professorships. Most of them became better writers because I made them write more than they would have on their own and on topics and within structures they would not have chosen. They developed efficiency and confidence along the way.

I know my process is ugly and I don’t want anyone seeing that mess. Not having to share first drafts is reassuring—indeed, essential—but writing from prompts is absolutely the most effective way to get myself writing, whether the prompt is from someone else or myself, even when the prompt is addressed in public. And especially when it is difficult. No one writes their best in their first draft, but in a generative workshop, challenging writing prompts are kind of the point.

For five years, I attended The Flight of the Mind, a weeklong workshop for women writers intended to commence new work. Writing prompts given by the women I studied under—Gish Jen, Molly Gloss, Lynne Sharon Schwartz, Janice Gould, and Charlotte Watson Sherman—allowed me to find the writer in myself. Sometimes I need that push. In reality, most of us do. Someone says go and then we do the work.

Don’t like prompts? Forced writing is “useless”? A waste of time? Pure laziness on the part of the instructor? Fine. Don’t attend that class if there is a choice. Go ahead and check out. But recognize that assignments and prompts were and remain critical to progress for many of us.

Perching birds must flap their wings to rise and unlock tendons that keep their toes wrapped around a branch. Sometimes writers are like that, our toes curled around safety. We may even need to be prompted to let go. Writing what I would not have thought of and in ways that are uncomfortable is useful, and makes me stronger, fueling both adrenaline high and undeniable terror. The courage to risk myself past fear pushes me toward the good stuff. It’s one way I take flight.

__

Jan Priddy‘s work has earned an Oregon Literary Arts Fellowship, Arts & Letters fellowship, Soapstone residency, Pushcart nomination, and numerous publications. An MFA graduate from Pacific University, she lives in the NW corner of her home state of Oregon, collects trash off the beach each day, and blogs at IMPERFECT PATIENCE: https://janpriddyoregon.wordpress.com

Wash Your Lyric (Essays): A Writing Prompt for a Strange Time

March 23, 2020 § 7 Comments

By Alex Marzano-Lesnevich

By Alex Marzano-Lesnevich

Maybe you’ve been able to get some writing done this past week, even focus. If so, I applaud you. I certainly haven’t. The situation, as we all know, changes by the hour, sometimes by the minute. What seemed unthinkable yesterday is the new normal; what seemed unthinkable last week—well, last week was a different era entirely.

I teach at Bowdoin College, which was and is on spring break, and which, when classes do resume next week, will switch to online-only for the remainder of the school year. With only a few necessary exceptions for those who don’t have anywhere else to go or have visa issues, students will not be returning to campus. I feel for them, especially the seniors whose college lives have evaporated with no chance at in-person goodbyes, and those whose home lives are unwelcoming or abusive. And I feel for them even more as they, and all of us, are subsumed into this whirl of uncertainty.

As an epidemiologist friend of mine put it, if the situation feels unprecedented in our lifetimes, it’s because it’s unprecedented in our lifetimes.

There is, in other words, plenty for us to think about. And so I will admit: I haven’t been thinking about writing.

When I emailed my students to check in, asking how they were and what I could do, I assumed they hadn’t been, either. But the responses came back: they’d like a writing prompt, please. A prompt like the kind I usually start each class with, a place for us to practice the making of art together, practice putting whatever is in our hearts and our minds and our memories to the page. And right now, a place for us to put all this uncertainty.

So for them, and for me, and all of us right now who could use a short assignment, a brief encouragement to acknowledge and feel this moment and turn it into art, here’s a writing exercise we can do together.

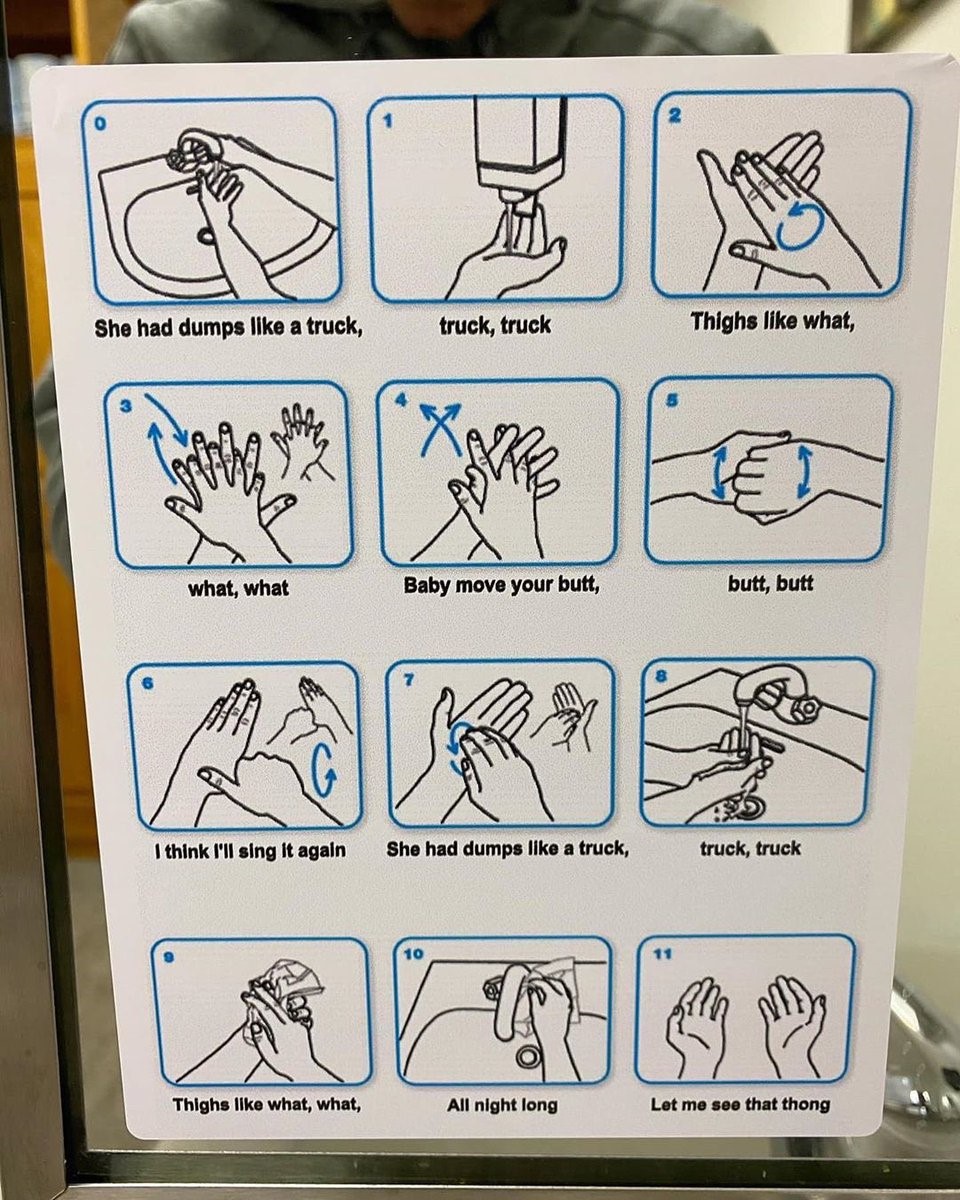

You’ve seen the handwashing diagrams, the ones intended to give us something—anything—else to sing beyond yet another rendition of Happy Birthday, many of them made through Wash Your Lyrics, a website created by 17-year-old William Gibson, using a poster from Britain’s National Health Service. Here’s one for Sisqo’s “Thong Song,” which I fully remember dancing to when I was my students’ age and 9/11 was still two years away, and we hadn’t yet had our worlds as disrupted as these kids just have:

Good, right? Makes you smile, keeps time while you keep safe. Gives you, in other words, a short assignment to keep your anxiety at bay.

Now try this:

I wish I knew whom to credit for turning Lucile Clifton’s poem “won’t you celebrate with me” into a handwashing diagram—it was making the rounds on Twitter—but when I saw it, something unlocked. It made me wonder: what if we treated the handwashing diagram as inspiration for a hermit crab essay?

In Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola’s Tell it Slant, they define a hermit crab essay as one in which the essayist borrows the form—the hard, hermit crab shell—from elsewhere in the world, and treats it as the container to shelter some deeply personal thing to be explored. “It is an essay that deals with material that seems born without its own carapace,” they write. “[M]aterial that is soft, exposed, and tender, and must look elsewhere to find the form that will best contain it.”

Soft, exposed, and tender—sound like anyone you know right now?

So for a prompt, try writing into the handwashing diagram, seeing what text you can pair with each step. (The Wash Your Lyrics website has a place for you to enter your own text.) What memories come up for you, as you write? What do the instructions suggest to your subconscious? And how can their orderly progression of steps shelter the disorderly progression of your thoughts in this time?

And—important, too—is there anywhere you want your essay to become less orderly? For the words to overspill the diagram? If that starts to happen, let it. Write into that uncertainty, and explore. What tension have you uncovered? What is at stake in your refusal, now, to be contained by the form? (For inspiration, here, try checking out Jill Talbot’s “The Professor of Longing,” in which the narrator’s life and anxieties gradually overspill the hermit crab form of a syllabus.)

Then take it further, beyond handwashing. Are there other found or hermit crab forms you can see in the world around you, in its response to the virus? Other forms you might use as inspiration for an essay? Perhaps one of those ubiquitous sales emails from a company talking about its virus response; or a text chain as you try to convince your loved ones to stay inside; or even instructions for a Zoom cocktail hour?

Have fun with it. Explore. A different form—a different short assignment—for each day.

I hope it becomes something that shelters you, as art must for all of us.

___

Alex Marzano-Lesnevich is an assistant professor at Bowdoin College and the author of THE FACT OF A BODY: A Murder and a Memoir. Their most recent piece was “Body Language” in the December 2019 Harper’s.

Author Photo by Greta Rybus

On Writing With Substance and Compassion

January 23, 2020 § 1 Comment

In her new craft essay, Mary Ann McSweeny illustrates why compassion should be one of the underlying components of all stories, and she explains how it is only when the writer remains a “detached witness” that compassion can flourish. McSweeny provides a list of questions and a brainstorming exercise for writers to immerse their characters and narrators in substance and compassion:

In her new craft essay, Mary Ann McSweeny illustrates why compassion should be one of the underlying components of all stories, and she explains how it is only when the writer remains a “detached witness” that compassion can flourish. McSweeny provides a list of questions and a brainstorming exercise for writers to immerse their characters and narrators in substance and compassion:

When I read my own work and that of others, I ask myself: Does the writer have compassion for the character on the page? Does the writer know the character’s life history, background, biography? Does the writer understand how the character has arrived at the point where the story begins? Has the writer somehow entered into the character’s struggle? With the personal “I” narrator: Does the writer portray the narrator’s struggle with an understanding of the narrator’s weaknesses, fears, or defects without trying to control the outcome of what’s happening?

Substance is not writing about compassion; it is writing with compassion so that the reader feels the writer’s authenticity.

Read the rest of this exceptional craft essay in our latest issue.

Teaching Brevity: Whetting the Appetite

September 25, 2017 § 7 Comments

By Frances Backhouse

By Frances Backhouse

Recently, while flipping through an Italian cookbook, it occurred to me that I’ve organized my third-year creative nonfiction workshop like an Italian meal. At twelve to thirteen weeks, with one three-hour class a week, it lasts longer than even the most leisurely Italian repast, but the structure is similar. During the first few classes, I serve up an array of bite-sized activities and assignments – the antipasto course, which both whets the students’ appetites and take the edge off their hunger while they’re busy writing first drafts of the pieces they’ll submit for workshopping. Once those drafts come to the table, we move onto the primo and secondo courses and spend the bulk of the term thoughtfully chewing our way through two essays per student. The last class is the dolce – a sweet, celebratory finale in which the students read excerpts from works they’ve written and polished over the term.

The part of this culinary metaphor that I want to expand on here is the antipasto course, specifically the ingredients provided by Brevity for the first assignment of the term. (But I’ll cease talking about food, so you don’t get hungry and wander off to the kitchen.) For this assignment, worth 10 percent of the course grade, each student chooses one essay from the collection of craft essays on the Brevity website and explores it through a short class presentation, plus a written reflection, due a few weeks after their presentation. Although both parts are mandatory, I grade only the written submission. I tell the students to think of the presentation as a preliminary articulation of their thoughts, with the class discussion offering ideas for refining them. My other instructions for the assignment are as follows:

The presentation should be about 15 minutes long: in the first 5 minutes you’ll tell us why you picked that essay and highlight what you consider to be the most interesting and important points; then you’ll lead us through a 10-minute discussion of the essay. Everyone is expected to read all of the essays in advance.

The written part of the assignment is a 750- to 900-word reflection. Begin with a brief overview or summary of your chosen essay (no more than one or two paragraphs). Then move on to a discussion of what you took away from reading this essay. For example: What questions did it answer for you? What questions did it raise? How did it inspire you? How did it challenge you? If you find the essay doesn’t offer you enough substance to feed 750 to 900 words of reflection, you may follow links in the essay or do your own research to expand on ideas raised by the essay. (If you go beyond the text of the original essay, include end-notes citing your additional sources.)

Typically, there are fifteen students in the course. I introduce the assignment during the first class and schedule five presentations for each of the next three classes.

The presentation sign-up is done online via CourseSpaces, my university’s learning management system. I give the students a couple of days to browse the Brevity website and then I open up a forum where they claim their preferred craft essay. Some of them leap in the moment the forum opens to ensure they get the piece they want, while others dither or procrastinate and finally settle on something just before the deadline. Banter often accompanies the choosing. “Damn you, Ellen! That was my first choice too,” one student wrote last year when someone else beat her to the essay “Go Ahead: Write About Your Parents, Again” (a perennial favorite). “Sniffed this one out,” wrote another as she announced her choice: “The Nose Knows: How Smells Can Connect Us to the Past and Lead Us to the Page.”

The beauty of allowing the students to choose their essays is that it let’s them take ownership of the learning process and pursue the topics that are of most interest to them. In past years, those whose first literary love is poetry have picked “What Can Sonnets Teach Us About Essays” and “Line Breaks: They’re Not Just For Poets Anymore.” A student mourning the loss of her grandmother opted for “Writing the Sharp Edges of Grief.” Another, who knew that revision was his weak point, challenged himself by choosing “Becoming Your Own Best Critic.” And the beguilingly titled “And There’s Your Mother Calling Out to You: In Pursuit of Memory” always gets snapped up quickly.

The students generally deliver insightful presentations and turn in intelligent written reflections. The quality of both writing and analysis varies, of course, but there’s enough evidence of engagement overall that I can easily count the assignment as a pedagogical success. However, the greatest merit may be in the discussions that follow the formal presentations. These free-flowing, student-initiated conversations often exceed the prescribed ten minutes and take us in unexpected but worthwhile directions, such as the lively debate about muses that followed a presentation on the essay “My Muse – He’s Just Not That Into Me.”

The value of these conversations is (at least) twofold: they get students thinking about craft in new ways; and they start building the bonds that are critical to effective workshopping. One particularly powerful case was a series of overlapping discussions about stereotyping, stigma and gender politics within the literary world that was prompted by three self-identified queer students’ presentations on “Writing Trans Characters,” “Mapping Identity: Borich’s Body Geographic” and “The Craft of Writing Queer.” But all of the discussions help lay the foundation for the sensitive work of peer-critiquing because they get the students talking about creative nonfiction in universal terms before they zero in on each other’s personal offerings.

If you’re teaching CNF, you’re welcome to add this assignment to your teaching menu. I’m sure you’ll find that Brevity’s pantry of craft essays holds plenty of delicious fare.

Buon appetito!

__

‘Teaching Brevity‘ is a special blog series celebrating the magazine’s 20th Anniversary, edited by Sarah Einstein. Read the other teaching posts here: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6.

___

Frances Backhouse teaches creative nonfiction at the University of Victoria and is the author of six nonfiction books, including Women of the Klondike and Once They Were Hats: In Search of the Mighty Beaver. Her short-form CNF has appeared most recently in the Bellingham Review and The New Territory.

This is Not to Say

September 22, 2009 § 1 Comment

Amy Lee Scott discusses the impulse behind her Brevity 31 essay, “This is Not To Say”:

Amy Lee Scott discusses the impulse behind her Brevity 31 essay, “This is Not To Say”:

I wrote this essay in response to a prompt my writing group assigned. Though I cannot fully recall the specifics of the prompt, I remember that it was on a topic situated somewhere between Lost Things and Nostalgia.

For a long time I had wanted to write an essay for the things that I never write about, the things that are lost by merit of being unsaid. This seemed like the perfect time to think it out. I also wanted to practice writing a sharp turn, something that would wield the essay from one emotional state to another by stitching memories together in an associative manner. This is surprisingly difficult to do in a short space, so I thought I would tackle the space issue by using a catalog.

Catalogs work hard, especially in small spaces. They can collate, categorize, and narrate in a way that other forms cannot. They can pinball from here to there, create an evocation of an emotion with few strokes, and hypnotize. The rich layers they accumulate can stun and delight and send a body reeling. On the flip side, they can seem shtick-y. Lazy. A bit too hip. Worse, they can feel pointless.

But for me, I had to take the risk. Sure, it wasn’t the kind of risk that saved lives from despicable ends, but it still had me mooning about with a big ol’ grin.

Words as Image: How “Thank You” Originated

January 6, 2014 § 3 Comments

I have often relied on objects and images to help convey meaning in my stories, poems, and essays. Perhaps over-relied. However, I also felt that I had found a way in to a telling a story that worked. In “Street Scene,” a lyric essay about a close friend who took her life, I found the image with resonance that knitted the essay together was that of the now-filled-in swimming pool of my childhood in my parents’ backyard. “Street Scene” is about remembering and grieving this friend, whom I met when she was in her thirties; the present tense of the essay is a week-long trip to Paris some years later, and the childhood pool initially seemed like a random out-of-place image. (She had never even seen the pool and we might never even have talked about it.)

My writing group pointed out that the pool and the associative memory of it that followed didn’t have anything to do with LeeAnne or the present-day of the narrator, who is walking around in Paris, but I felt stubborn about the pool, and refused to give it up. I worked on this essay for over two years (I have a patient and kind writing group), and with the wise suggestions of the editor of the literary journal that published it, the image emerged and quietly grew to be the central image of childhood, the past, and my longing for LeeAnne’s return. The image of the pool was the right one, but I had had to trust it and also, to learn to trust myself. Writing and completing “Street Scene” gave me the confidence to trust myself.

My essay in the September 2013 issue of Brevity, “Thank You,” is unlike anything else I’ve ever written in that the two words themselves become what is usually an image in my writing—a touchstone, a repeated phrase, a symbol, a talisman, a warning, an entreaty, an objective correlative, a prayer, a plea, a longing, a wish. Voice and imagery have traditionally driven my writing. In both the fiction and nonfiction I’ve written, I have never used a lot of dialogue. I think of writing assignments that ask students to overhear and record bits of dialogue in restaurants, in coffee shops, on trains, in line at stores, in line anywhere. As a teacher, I’ve given these assignments myself, but often haven’t taken the advice to listen closely, myself, and to write down what I hear.

When writing “Thank You,” (the whole first draft came out in one rush—it was a gift), I mused on how often the man in the essay and I said “thank you” to each other, but when I expected and wanted to hear thank you the most, the words never came. The title of the essay and the essay itself would not have worked without the sentence from the young daughter. The little girl’s father and I both thought it was an odd and funny thing for his daughter to say: I love this book so much I’m not going to say thank you. I am intrigued by the gap between what we say and what we feel or think we feel. When I showed an early draft to a few other writers, at least one was puzzled by the title. Who is saying thank you?, she asked. And what is she (the narrator/me) thankful about? He is gone, I never met the daughter, but the words and story stayed with me. I am thankful for that.

Writing Prompt: Many essays, stories, and poems I’ve written are letters to people I have loved or people who haunt me—these are letters I am unable or unwilling to send. “Thank You,” is one of those letters. Write a letter that you can never send or will never send—to someone with whom you are not in touch, or who has passed, or to whom the ability to speak at a certain level or pitch has faded. Who are the people who haunt you and what would you say that you never had a chance to say, if you could say it? A brief essay in the form of a letter, a direct address, a wish.

—

Sejal Shah’s writing has recently appeared or is forthcoming in The Kenyon Review Online, The Literary Review, Web Conjunctions, and AWP’s The Writer’s Chronicle. She lives and teaches in Upstate New York. Find her online at www.sejal-shah.com.

Share this: